RE: Consultation Draft – Radio Spectrum Five Year Outlook 2012-2016

Dear Minister,

I agree with the government’s goal of growing New Zealand’s economy and I am glad a link between effective radio spectrum management and New Zealand’s prosperity has been made in the introduction to MBIE’s Radio Spectrum Five Year Outlook 2012-2016.

Five years is a long time in the world of technology. In June of 2007, just five years ago, the first iPhone was released. The iPhone and its competitors have changed forever the way people interact with their phones and mobile data. This year, 3G smartphones are used by 50% of New Zealanders. Smartphones are poised to have a tremendous impact on New Zealand’s economy, with huge potential to streamline communications in the agriculture and tourism sectors.

In 2007 the most recent IEEE standards for 802.11 Wi-Fi allowed speeds up to 54mbps. This year the first 802.11ac Wi-Fi chipsets shipped to customers, at 867mbps. Due to light regulations and scarcity of spectrum, Wi-Fi devices are best in class when it comes to spectral efficiency and interference rejection, while having a lower cost per chipset than 3g/4g competitors. Wi-Fi is a part of almost every mobile device on the market, and is used daily at home and across all key industries. In the last five years, Wi-Fi has had an unquestionable impact on New Zealand’s economy.

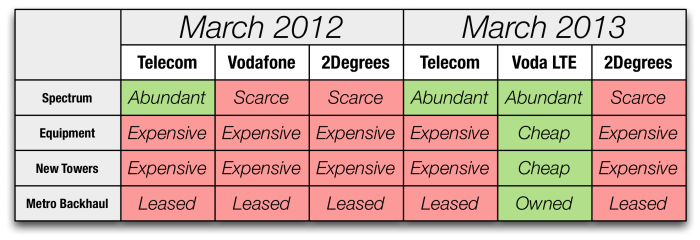

Five years has brought New Zealand a new mobile carrier, but one who operates with a fraction of the spectrum tied up by incumbent carriers, not all of whom use their spectrum. As a result of the entry of 2Degrees, the cost of mobile services has dropped precipitously, and New Zealand consumers and businesses are reaping the advantages of affordable mobility.

Smartphones, Wi-Fi, and a third cellular carrier have emerged notwithstanding Radio Spectrum Management policies, legislation or changes to those over the past five years. They have developed within the bounds of very small blocks of radio spectrum when compared to traditional uses such as radio and television uses. They have shown that they are extremely efficient users of the spectrum, but all would benefit from access to more spectrum, and more effective spectrum management.

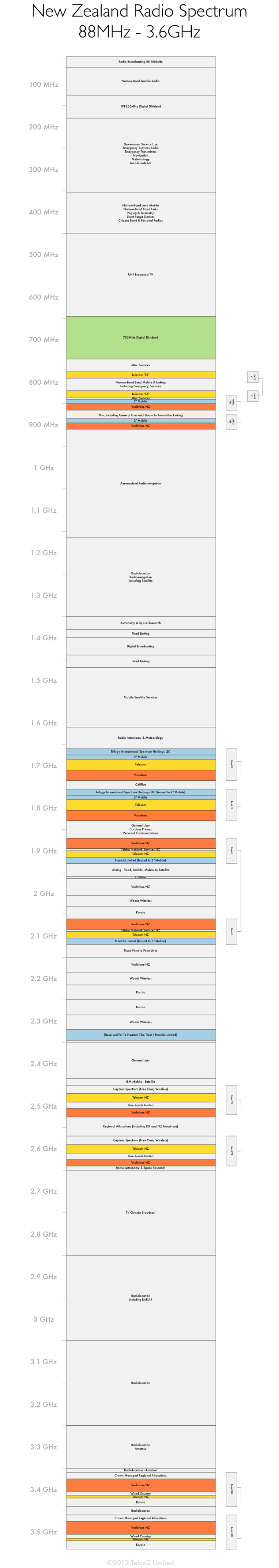

Measurements taken by University of Auckland researchers Chiang, Rowe, & Sowerby (2007) showed that in Auckland, arguably New Zealand’s busiest radio spectrum environment, real spectrum use in 806-2750MHz was only 6.2%. These measurements included all of the cellular and most popular broadband bands. Almost 94% of the New Zealand’s most valuable radio spectrum was quiet it its largest market. This is hardly effective management.

Taken in isolation, the UoA study might seem fantastic or flawed. Viewed in the context of studies around the world including the US and Singapore, some funded by the United States Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency, these measurements are unsurprising. It has been conclusively proven that traditional management techniques do not result in effective use of the radio spectrum.

Tradition, unfortunately, originates from New Zealand.

New Zealand’s pioneering approach to treat spectrum as a property right (based on the Torrens land title system) was based on a 1988 report by London consultancy NERA. Their work in turn was highly influenced by the ideas of Ronald Coase, who in a 1959 paper equated spectrum use to land use, and considered that users who would pay the most for exclusive rights to spectrum would put that spectrum to the best use.

It is unlikely that Coase or Charles Jackson, a key NERA consultant involved in writing the report, envisioned that treating spectrum as a property right would result in the massive inefficiencies we see in New Zealand today.

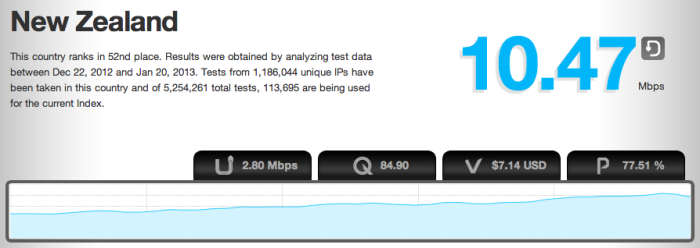

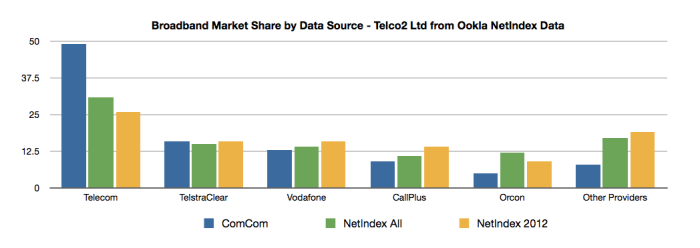

It has however happened. For a sum of money enough to block smaller competitors, some companies have locked up radio spectrum for years that would have a far greater impact on New Zealand’s economy if in use than the price they paid at auction. As a result of locking up the spectrum, these companies have been able to create an artificial scarcity. They have been able to use a limited amount of spectrum and equipment to provide services, while guaranteeing they were the only game in town. Resulting services and pricing, when compared to Australia or other OECD peers, has been poor for New Zealand.

The best result for the owner of the property has not aligned with growing New Zealand’s economy.

In the Five Year Outlook document, it’s stated that “the key operational objectives of spectrum management in New Zealand are to enable productive radio applications and minimise harmful interference between uses.” If this is the case, Radio Spectrum Management should be investigating ways of enabling productive radio applications as its highest priority – above asset management, documentation reviews, compliance projects, fee reviews, and above any legislative change that would further entrench the existing system of spectrum as an exclusive property right.

Section 4.1.3 of the Outlook document holds the key to efficient, productive, and full use of the radio spectrum. Cognitive radio technologies were created to take advantage of unused radio spectrum. They end the possibility of gaming the telecommunications market by purchasing and then not using radio spectrum. And while the Outlook assumes the technology is unlikely to develop within the next five years, the reality is cognitive radio is here and available today. Chipset manufacturers including Texas Instruments already offer DSP products capable of implementing cognitive radio (including IEEE 802 standards) and commercial cognitive radio networks are in use in the United States today.

The Outlook states of cognitive radio that “facilitation of the technology may require a radical departure from existing methods of spectrum regulation”. The time for a radical departure is now, and the concept that must be introduced to radio spectrum legislative and management frameworks is that of Primary and Secondary Use.

Primary Users have existing spectrum licenses which commonly allow for the right to transmit on a frequency and the right to have no harmful interference on that frequency. A primary user with a national management right could install transmitters around the country have interference-free operation everywhere they transmitted and everywhere their radio signals could reach. Their rights to offer a service would not be impeded upon.

Secondary Users are those with rights to transmit on frequencies only when their transmission would not affect a primary user, and with no protection from harmful interference on a particular frequency. Secondary Users can exist and thrive in areas where Primary Users cannot or will not, for either economic or technical reasons, use the spectrum they have licensed. Secondary use is an extremely good way of ensuring radio spectrum is used effectively.

The cognitive radio technologies now standardised by IEEE are advanced technologies that are capable of allowing safe coexistence of Primary and Secondary Users. They are likely to be adopted across all forms of radiocommunications, as innovative users meet with artificial spectrum shortages created by property rights based management and adapt to effectively communicate. In five years, cognitive radio products will not be an emerging technology, they will be a commonplace one.

The growth of New Zealand’s economy is linked to its ability to effectively communicate – not just with existing technologies, but with what’s next. Radio technology is changing faster than we can forecast on a five year time scale. We can’t reliably predict the next iPhone, Wi-Fi, or entrant into the New Zealand telecommunications market. We can predict that with so much of the world’s radio spectrum sold off but under-utilised, what’s next is likely to include cognitive radio.

The greatest impact Radio Spectrum Management could have on the economy is by ensuring management frameworks are ready for cognitive radio products. Such products will lead to greater, more efficient, lower cost communications, benefiting New Zealand in innumerable ways.

I thank you for this opportunity to comment on Radio Spectrum Management’s Consultation Draft – Radio Spectrum Five Year Outlook 2012-2016 and invite you to contact me if you have any questions regarding my submission.

Regards,

Jonathan Brewer